How Does Memory for AI Agents Work?

The 4 memory types every AI agent needs

Welcome to the AI Agents Foundations series: A 9-part journey from Python developer to AI Engineer. Made by busy people. For busy people.

Everyone’s talking about AI agents. But what actually is an agent? When do we need them? How do they plan and use tools? How do we pick the correct AI tools and agentic architecture? …and most importantly, where do we even start?

To answer all these questions (and more!), We’ve started a 9-article straight-to-the-point series to build the skills and mental models to ship real AI agents in production.

We will write everything from scratch, jumping directly into the building blocks that will teach you “how to fish”.

What’s ahead:

AI Agent’s Memory ← You are here

By the end, you’ll have a deep understanding of how to design agents that think, plan, and execute—and most importantly, how to integrate them in your AI apps without being overly reliant on any AI framework.

Let’s get started.

Opik: Open-Source LLMOps Platform (Sponsored)

This AI Agents Foundations series is brought to you by Opik (created by Comet), the LLMOps open-source platform used by Uber, Etsy, Netflix, and more.

Comet, through its free events, is dedicated to helping the AI community keep up on the state-of-the-art LLMOps topics, such as:

AI observability: evaluating and monitoring of LLM apps

Detecting hallucinations

Defining custom AI evals for your business use case

These are old problems… But applying them in production isn’t! There is constant progress in all these dimensions.

That’s why Comet constantly offers free events on how to solve LLMOps problems in production, hands-on, with tools and strategies for LLM evaluation, experiment tracking, and trace monitoring, so you can properly move from theory to shipping AI apps.

You can check out their free events on LLMOps here:

The next ones are on the 7th of December on AI observability and on the 17th of December on hallucinations. Both are looking over state-of-the-art papers on how to solve these problems. Enjoy!

AI Agent’s Memory

One year ago at ZTRON, we faced a challenge that many AI builders encounter: how do we give our agent access to the right information at the right time? Like most teams, we jumped straight into building a complex multimodal Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system. We built the whole suite: embeddings for text, embeddings for images, OCR, summarization, chunking, and multiple indexes.

Our ingestion pipeline became incredibly heavy. It introduced unnecessary complexity around scaling, monitoring, and maintenance. At query time, instead of a straight line from question to answer, our agent would zigzag through 10 to 20 retrieval steps, trying to gather the right context. The latency was terrible, costs were high, and debugging was a nightmare.

Then we realized something essential. Because we were building a vertical AI agent for a specific use case, our data wasn’t actually that big. Through virtual multi-tenancy and smart data siloing, we could retrieve relevant data with simple SQL queries and fit everything comfortably within modern context windows—around 65,000 tokens maximum, well within Gemini’s 1 million token input capacity.

We dropped the entire RAG layer in favor of Context-Augmented Generation (CAG) with smart context window engineering. Everything became faster, cheaper, and more reliable. This experience taught me that the fundamental challenge in building AI agents isn’t just about retrieval. It is about understanding how to architect memory systems that match your actual use case.

The core problem we are solving is the fundamental limitation of LLMs: their knowledge is vast but frozen in time. They are unable to learn by updating their weights after training, a problem known as “continual learning” [1]. An LLM without memory is like an intern with amnesia. They might be brilliant, but they cannot recall previous conversations or learn from experience.

To overcome this, we use the context window as a form of “working memory.” However, keeping an entire conversation thread plus additional information in the context window is often unrealistic. Rising costs per turn and the “lost in the middle” problem—where models struggle to use information buried in the center of a long prompt limit this approach. While context windows are increasing, relying solely on them introduces noise and overhead [2].

Memory tools act as the solution. They provide agents with continuity, adaptability, and the ability to “learn” without retraining. When we first started building agents, working with 8k or 16k token limits forced us to engineer complex compression systems. Today, we have more breathing room, but the principles of organizing memory remain essential for performance.

In this article, we will explore:

The four fundamental types of memory for AI agents.

A detailed look at long-term memory: Semantic, Episodic, and Procedural.

The trade-offs between storing memories as strings, entities, or knowledge graphs.

The complete memory cycle, from ingestion to inference.

The 4 Memory Types for AI Agents

To build effective agents, we must distinguish between the different places information lives. We can borrow terms from biology and cognitive science to categorize these layers useful for engineering.

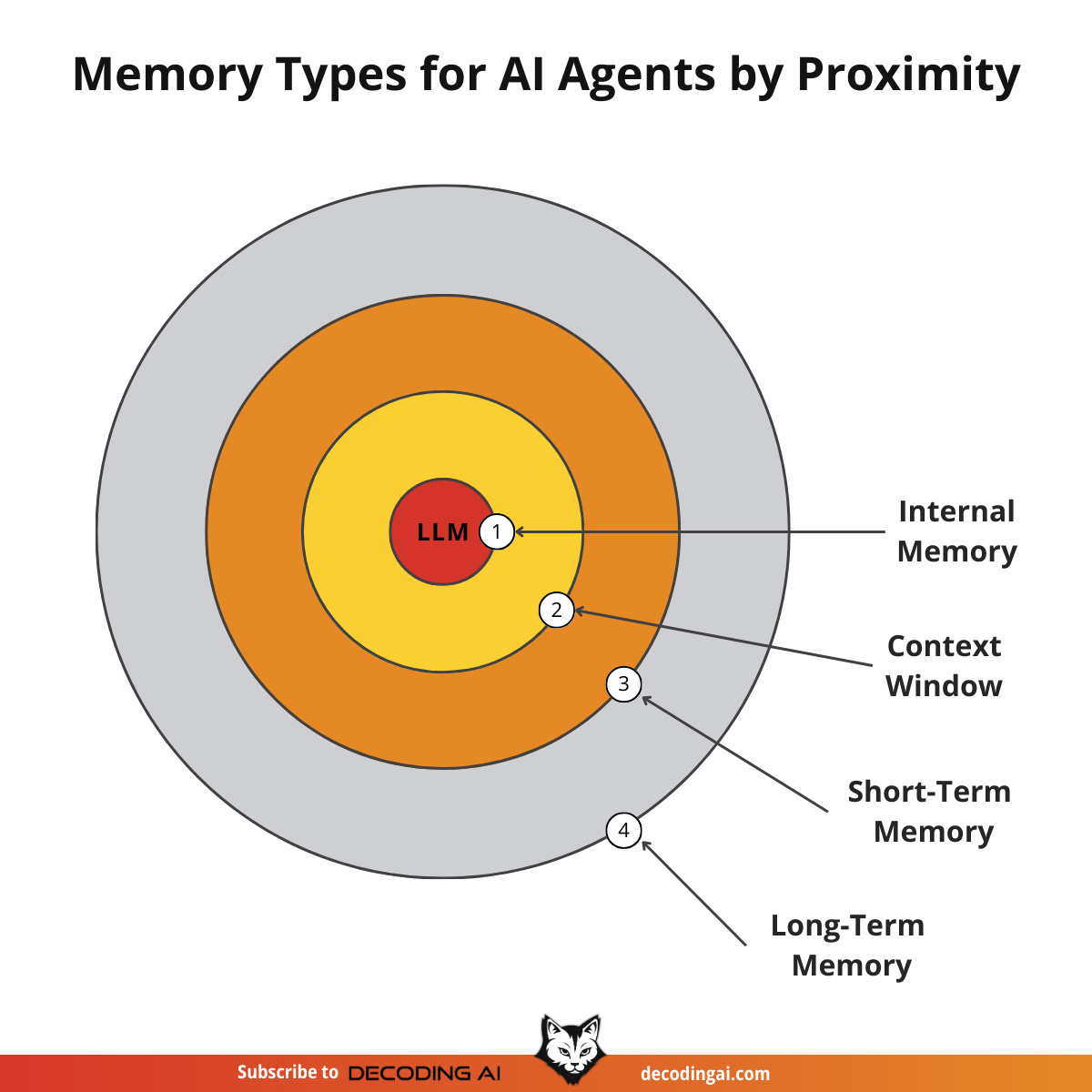

There are four distinct memory types based on their persistence and proximity to the model’s reasoning core.

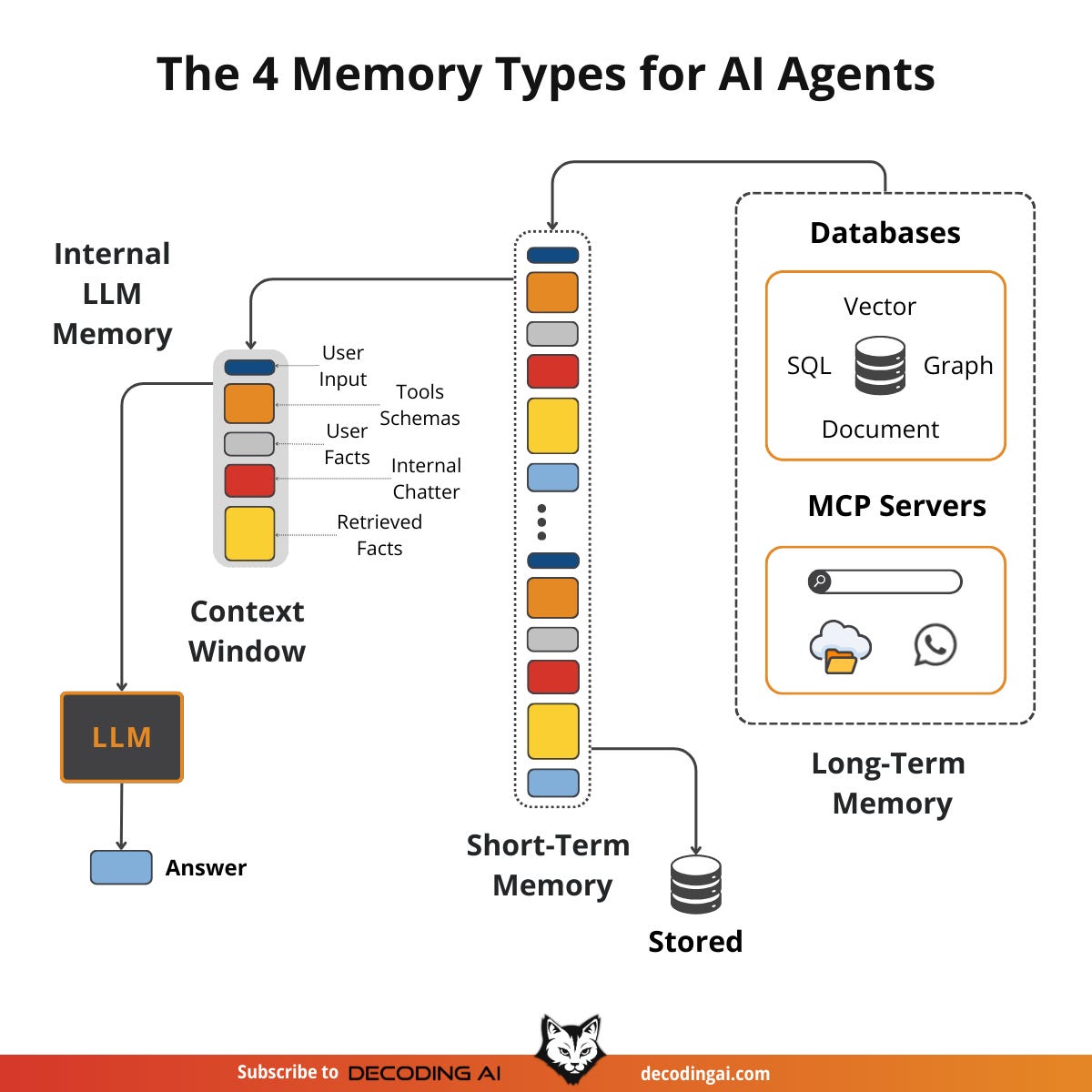

1. Internal Knowledge: This is the static, pre-trained knowledge baked into the LLM’s weights. It is the best place to store general world knowledge—models know about whole books without needing them in the context window. However, this memory is frozen at the time of training.

2. Context Window: This is the slice of information we pass to the LLM during a specific call. It acts as the RAM of the LLM. It is the only “reality” the model sees during inference.

3. Short-Term Memory: This is the RAM of the entire agentic system. It contains the active context window plus recent interactions, conversation history, and details retrieved from long-term memory. We slice this short-term memory to create the context window for a single inference step. It is volatile and fast, simulating the feeling of “learning” during a session [3].

4. Long-Term Memory: This is the external, persistent storage system (disk) where an agent saves and retrieves information. This layer provides the personalization and context that internal knowledge lacks and short-term memory cannot retain [4].

The dynamic between these layers creates the agent’s intelligence. First, part of the long-term memory is “retrieved” and brought into short-term memory. This retrieval pipeline queries different memory types in parallel. Next, we slice the short-term memory into an active context window through context engineering. Finally, during inference, the LLM uses its internal weights plus the active context window to generate output.

Another useful way to visualize this is by proximity to the LLM. Internal memory is intrinsic, while long-term memory is the furthest away, requiring specific retrieval mechanisms to become useful.

Categorizing memory this way is critical for engineering. Internal knowledge handles general reasoning. Short-term memory manages the immediate task. Long-term memory handles personalization and continuity. No single layer can perform all three functions effectively. To better understand long-term memory, we can further apply cognitive science definitions to specific data types.

Long-Term Memory: Semantic, Episodic, and Procedural

Long-term memory is not a single bucket of text. It consists of three distinct types, each serving a different role in making an agent “intelligent” [5], [6].

Semantic Memory (Facts & Knowledge)

Semantic memory is the agent’s encyclopedia. It stores individual pieces of knowledge or “facts.” These can be independent strings, such as “The user is a vegetarian,” or structured attributes attached to an entity, like {”food restrictions”: “User is a vegetarian”}. This is where the agent stores concepts and relationships regarding specific domains, people, or places.

The primary role of semantic memory is to provide a reliable source of truth. For an enterprise agent, this might involve storing internal company documents or technical manuals. For a personal assistant, semantic memory builds a persistent user profile. It recalls specific preferences like {”music”: “User likes rock music”} or constraints like {”dog”: “User has a dog named George”}. This allows the agent to retrieve relevant facts without searching through a noisy conversation history.

Let’s look at how we can implement semantic memory using mem0, an open-source memory library.

We define a helper function to add text to memory and categorize it.

def mem_add_text(text: str, category: str = “semantic”, **meta) -> str:

“”“Add a single text memory. No LLM is used for extraction or summarization.”“”

metadata = {”category”: category}

for k, v in meta.items():

if isinstance(v, (str, int, float, bool)) or v is None:

metadata[k] = v

else:

metadata[k] = str(v)

memory.add(text, user_id=MEM_USER_ID, metadata=metadata, infer=False)

return f”Saved {category} memory.”We insert specific facts about the user.

facts: list[str] = [

“User prefers vegetarian meals.”,

“User has a dog named George.”,

“User is allergic to gluten.”,

“User’s brother is named Mark and is a software engineer.”,

]

for f in facts:

print(mem_add_text(f, category=”semantic”))We can now search for this specific semantic information.

results = memory.search(”brother job”, user_id=MEM_USER_ID, limit=1)

print(results[”results”][0][”memory”])It outputs:

User’s brother is named Mark and is a software engineer.Episodic Memory (Experiences & History)

Episodic memory is the agent’s personal diary. It records past interactions, but unlike timeless facts, these memories have a timestamp. It captures “what happened and when.”

This memory type is essential for maintaining conversational context and understanding relationship dynamics. A semantic fact might be “User is frustrated with his brother.” An episodic memory would be: “On Tuesday, the user expressed frustration that their brother, Mark, always forgets their birthday. I provided an empathetic response. [created_at=2025-08-25].”

This “episode” provides nuanced context. If the topic comes up again, the agent can say, “I know the topic of your brother’s birthday can be sensitive,” rather than just stating a fact. It also allows the agent to answer questions like “What happened last week?” [7].

Here is how we can implement episodic memory by compressing a conversation into a summary.

We define a dialogue and ask the LLM to summarize it into an episode.

dialogue = [

{”role”: “user”, “content”: “I’m stressed about my project deadline on Friday.”},

{”role”: “assistant”, “content”: “I’m here to help—what’s the blocker?”},

{”role”: “user”, “content”: “Mainly testing. I also prefer working at night.”},

{”role”: “assistant”, “content”: “Okay, we can split testing into two sessions.”},

]

episodic_prompt = f”“”Summarize the following 3–4 turns as one concise ‘episode’ (1–2 sentences).

Keep salient details and tone.

{dialogue}

“”“

episode_summary = client.models.generate_content(model=MODEL_ID, contents=episodic_prompt)

episode = episode_summary.text.strip()We save this summary as an episodic memory.

print(

mem_add_text(

episode,

category=”episodic”,

summarized=True,

turns=4,

)

)We can search for the “experience” later.

hits = mem_search(”deadline stress”, limit=1, category=”episodic”)

for h in hits:

print(f”{h[’memory’]}\n”)It outputs:

A user, stressed about a Friday project deadline because of testing and a preference for working at night, is advised to split the testing work into two manageable sessions.Procedural Memory (Skills & How-To)

Procedural memory is the agent’s muscle memory. It consists of skills, learned workflows, and “how-to” knowledge. It dictates the agent’s ability to perform multi-step tasks.

This memory is often baked into the agent’s system prompt as reusable tools or defined sequences. For example, an agent might store a MonthlyReportIntent procedure. When a user asks for a report, the agent retrieves this procedure: 1) Query sales DB, 2) Summarize findings, 3) Email user. This makes behavior reliable and predictable. It encodes successful workflows so the agent doesn’t have to reason from scratch every time [8].

We define a procedure as a text block containing steps.

procedure_name = “monthly_report”

steps = [

“Query sales DB for the last 30 days.”,

“Summarize top 5 insights.”,

“Ask user whether to email or display.”,

]

procedure_text = f”Procedure: {procedure_name}\nSteps:\n” + “\n”.join(f”{i + 1}. {s}” for i, s in enumerate(steps))

mem_add_text(procedure_text, category=”procedure”, procedure_name=procedure_name)We retrieve the procedure by intent.

results = mem_search(”how to create a monthly report”, category=”procedure”, limit=1)

if results:

print(results[0][”memory”])It outputs:

Procedure: monthly_report

Steps:

1. Query sales DB for the last 30 days.

2. Summarize top 5 insights.

3. Ask user whether to email or display.

Now that we know what to save, we must decide how to store it.

Storing Memories: Pros and Cons of Different Approaches

The way an agent’s memories are stored is an architectural decision that impacts performance, complexity, and scalability. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Let’s explore the three primary methods we experiment with as AI Engineers.

1. Storing Memories as Raw Strings

This is the simplest method. Conversational turns or documents are stored as plain text and indexed for vector search.

Pros: It is simple and fast to set up, requiring minimal engineering. It preserves nuance, capturing emotional tone and linguistic cues without loss in translation.

Cons: Retrieval is often imprecise. A query like “What is my brother’s job?” might retrieve every conversation mentioning “brother” and “job” without pinpointing the current fact. Updating is difficult; if a user corrects a fact (“My brother is now a doctor”), the new string just adds to the log, creating potential contradictions. It also lacks structure, making it hard to distinguish state changes over time (e.g., “Barry was CEO” vs. “Claude is CEO”).

2. Storing Memories as Entities (JSON-like Structures)

Here, we use an LLM to transform messy interactions into structured memories, stored in formats like JSON within document databases (MongoDB) or SQL databases (PostgreSQL).

Pros: It allows for precise, field-level filtering (e.g., “user”: {”brother”: {”job”: “Software Engineer”}}). The agent can retrieve specific facts without ambiguity. Updates are easier. You simply overwrite the relevant field. This is ideal for semantic memory like user profiles or preferences.

Cons: It requires upfront schema design complexity. Still, tt can be rigid. If the agent encounters information that doesn’t fit the schema, that data might be lost unless the schema is updated [9].

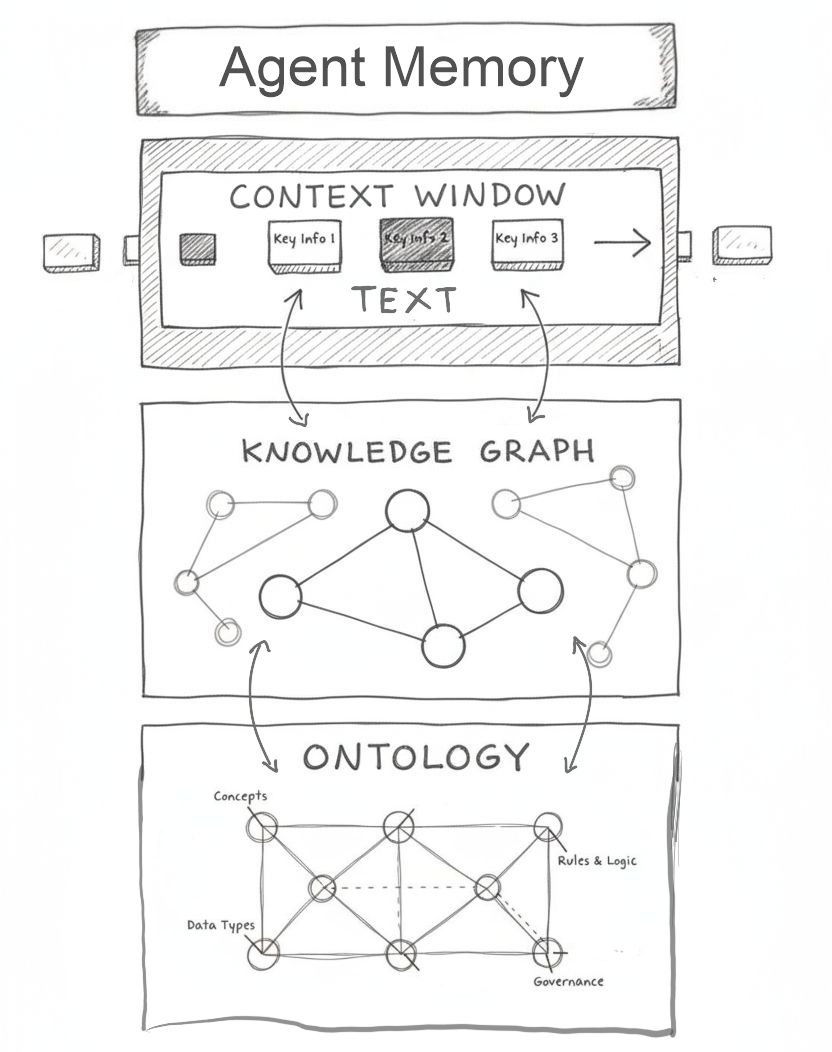

3. Storing Memories in a Knowledge Graph

This is the most advanced approach. Memories are stored as a network of nodes (entities) and edges (relationships) using databases such as Neo4j or PostgreSQL.

Pros: It excels at representing complex relationships (e.g., (User) -> [HAS_BROTHER] -> (Mark)). It offers superior contextual and temporal awareness by modeling time as a property of a relationship (e.g., [RECOMMENDED_ON_DATE]). Retrieval is auditable. You can trace the path of reasoning, which builds trust.

Cons: It has the highest complexity and cost. Converting unstructured text into graph triples is difficult. Graph traversals can be slower than vector lookups, potentially impacting real-time performance. For simple use cases, it is often overkill [10].

💡 Note: Vector databases are typically document databases with vector indexes. They are excellent for retrieval but, in terms of storage structure, they usually fall into the “raw strings” or “entities” bucket (2nd option).

The choice should be guided by your product’s needs. Start simple and evolve as complexity grows.

Memory cycles: From Long-Term to Internal Memory

How do these memory types work together? They operate as a single clockwork system.

User Input: We start with the user input, which triggers the entire system.

Ingestion: Long-term memory is populated by data pipelines or RAG ingestion. External data is accessed via APIs or Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers.

Retrieval: Data is pulled from long-term memory into short-term memory using search tools.

Short-Term Assembly: Short-term memory is populated with facts from long-term memory, user input, LLM’s internal chatter and output, and the current tool schemas.

Context Engineering: We slice the short-term memory to fit the context window. If a user asks about Nvidia, we trim facts about other companies. This projection from the short-term memory to the context window is part of the art of context engineering.

Inference: We pass this context window to the LLM. The answer is generated based on this window plus the LLM’s internal knowledge. This is their reality.

Loop: The output of the LLM is added back to the short-term memory.

Update - From Short-Term Memory: Based on any new facts about the user and problem at hand, we can further update the long-term memory with user preferences and facts, such as what companies they like.

Update - From External World: Meanwhile, the long-term memory can constantly be updated with other facts from the data pipelines.

Persistence: Finally, the short-term memory can be saved to a database to remember context between multiple user sessions.

Conclusion

Memory is the component that transforms a stateless chat application into a personalized agent. It is the current engineering solution to the problem of continual learning. By constantly engineering the context window (the LLM’s reality) we allow agents to “learn” and adapt over time.

Remember that this article is part of a longer series of 9 pieces on the AI Agents Foundations that will give you the tools to morph from a Python developer to an AI Engineer.

Here’s our roadmap:

AI Agent’s Memory ← You just finished this one.

Multimodal Data ← Move to this one

See you next Tuesday.

What’s your take on today’s topic? Do you agree, disagree, or is there something I missed?

If you enjoyed this article, the ultimate compliment is to share our work.

Go Deeper

Everything you learned in this article, from building evals datasets to evaluators, comes from the AI Evals & Observability module of our Agentic AI Engineering self-paced course.

Your path to agentic AI for production. Built in partnership with Towards AI.

Across 34 lessons (articles, videos, and a lot of code), you’ll design, build, evaluate, and deploy production-grade AI agents end to end. By the final lesson, you’ll have built a multi-agent system that orchestrates Nova (a deep research agent) and Brown (a full writing workflow), plus a capstone project where you apply everything on your own.

Three portfolio projects and a certificate to show off in interviews. Plus a Discord community where you have direct access to other industry experts and me.

Rated 4.9/5 ⭐️ by 190+ early students — “Every AI Engineer needs a course like this.”

Not ready to commit? We also prepared a free 6-day email course to reveal the 6 critical mistakes that silently destroy agentic systems. Get the free email course.

Thanks again to Opik for sponsoring the series and keeping it free!

If you want to monitor, evaluate and optimize your AI workflows and agents:

References

Wang, L., Zhang, X., Su, H., & Zhu, J. (2025). A Comprehensive Survey of Continual Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.00487. https://arxiv.org/html/2510.17281v2

Liu, N. F., Lin, K., Hewitt, J., Paranjape, A., Bevilacqua, M., Petroni, F., & Liang, P. (2023). Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03172. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.03172

What is AI agent memory?. (n.d.). IBM. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/ai-agent-memory

Iusztin, P. (2024, May 21). Memory: The secret sauce of AI agents. Decoding AI Magazine. article

Sumers, T. R., Yao, S., Narasimhan, K., & Griffiths, T. L. (2023). Cognitive Architectures for Language Agents. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/html/2309.02427

Griciūnas, A. (2024, October 30). Memory in Agent Systems. SwirlAI Newsletter. article. article

Whitmore, S. (2025, June 18). What is the perfect memory architecture?. YouTube. video

Mem^p: A Framework for Procedural Memory in Agents. (n.d.). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/html/2508.06433v2

Chalef, D. (2024, June 25). Memex 2.0: Memory The Missing Piece for Real Intelligence. Substack. article

Chhikara, P. (2025). Mem0: Building Production-Ready AI Agents with Scalable Long-Term Memory. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/html/2504.19413

Images

If not otherwise stated, all images are created by the author.

“Pros: It allows for precise, field-level filtering (e.g., “user”: {”brother”: {”job”: “Software Engineer”}}). The agent can retrieve specific facts without ambiguity. Updates are easier. You simply overwrite the relevant field. This is ideal for semantic memory like user profiles or preferences.”

Agree. I think the pros outweigh the cons, because it’s mostly just a little upfront work to get it going. This is how I stored data for my rag. Great post thanks.

Thanks for memory management planning on the same for the good 😊